By Jody Clark

They say that for every complex social problem there is always a solution that is clear, simple and wrong and nowhere is this truer than for drug-related deaths. The accepted wisdom is that to reduce drug-related deaths people simply need to stop using drugs - no drug use, no overdoses, no deaths. Simple, done, move on to proper social problems. After all, this has been Government policy since 2010 and if it wasn’t for UK citizens refusing to comply with this clear and simple directive, deaths would have all but disappeared.

The only problem is that people seem to want to use drugs. Whether it’s the legal variety or those for which possession is prohibited, substance use remains a familiar part of the human experience. People who use drugs do so for a broad spectrum of reasons, be it for pleasure, relaxation or experimentation, some to enhance experiences, increase social connectedness and empathy and, of course, those who use drugs to deal with a life of pain and trauma. Often it's a mix of reasons but whether we like it or not, people who use drugs derive a benefit from doing so – regardless of whether it looks from outside that there is only a negative impact or whether we judge the risk as too high.

All overdose deaths are tragedies, whether it's a teenager dying after using MDMA at a festival or a middle-aged man from a heroin overdose in a hostel. It’s understandable that the media widely covers the loss of young people dying from MDMA use, despite these only making up a small number of the overall fatalities. Children dying before they reach their prime is heart-breaking and the coverage of these deaths is increasingly sensitive and often seeks to capture the essence of the person who has been lost to us. Families and friends have been able to share their memories and reflect on the futures that are no longer possible.

Unfortunately, the same is not true of heroin-related deaths. Media articles, if any even appear, remain full of stigmatising language, usually referring to the "addict" that has died, focusing on the drug use and the failure of the individual to have stopped. Rarely, if ever, do articles look at the person, their history, what they may have had to overcome in their lives - just one less junkie being a drain on society. We've got an increasing understanding of the role of trauma and adverse childhood experiences that underpin many people's heroin use but the media continue to push stories that paint the deceased as merely lacking the necessary willpower or moral fibre to stop.

Deaths from MDMA and other club drugs have been mainly due to very high purity putting people at risk of taking an unknowingly dangerous dose. Without legally regulated production and supply of these substances, it is left to organisations such as The Loop to offer drug testing facilities to give individuals an opportunity to better understand what it is they have bought and to sit with a health professional to better understand the risks and allow informed choices to be made.

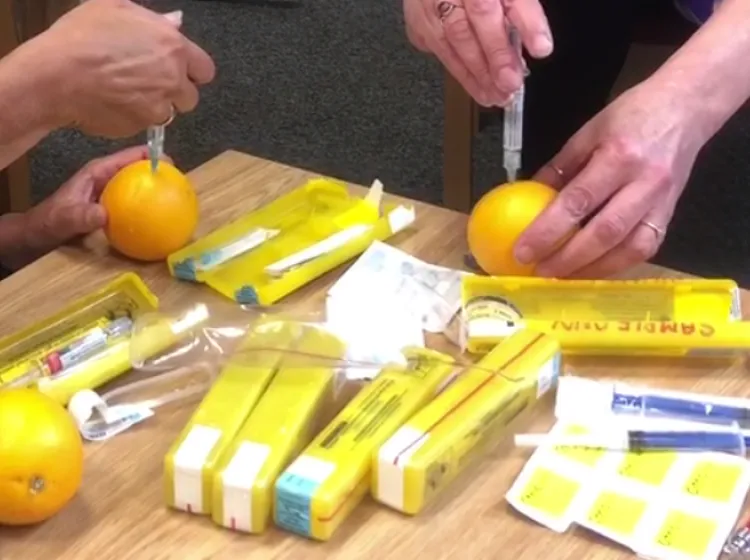

These measures, while still underfunded and under-supported by local and central government, have been widely accepted as a public good, and are relatively uncontroversial. However, the response to reducing opiate deaths has so far been much more lacklustre. Naloxone, the opiate overdose reversal drug, should now be easily available through drug services and has been saving lives up and down the country. Whilst naloxone doesn’t prevent overdoses, just reduces the risk of them being fatal, without it there would be far more deaths. However, it is crucial we don’t solely rely on the supply of this emergency medication to prevent people from dying.

To reduce opiate deaths, there are things we can do right now: prioritise access to and retention in treatment, ensure people aren’t booted out of treatment for relatively minor non-compliance, provide decent doses of substitute medication for a decent length of time, as well as increasing availability of naloxone wherever people are using opiates. Improvements to these alone would save a significant number of lives.

If drug-related deaths continue along the same trend that we’ve seen since 2009, we would expect 90,000+ deaths attributed to drug misuse over the next 20 years, with opiates making up the bulk of these. At some point you'd hope this would be recognised as the public health emergency it already is. There are things that could be introduced very quickly that would further reduce the rate of deaths. Just like drug safety testing first took place on the continent before the UK, other initiatives provided in Europe and elsewhere have been proven to reduce the number of deaths related to opiate use and we should adopt them where there is the need to.

Heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) is the provision of pharmaceutical grade heroin for use in a clinical environment under medical supervision. HAT is available in Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, Canada and Denmark to reduce the harms associated with heroin use. Ironically, it’s based on the old “British System” of prescribing heroin and other controlled drugs to the middle class, which all but ceased decades ago. Deaths, crime and anti-social behaviour have all reduced where HAT has been introduced and is far more effective than the mainstream drug treatment currently available. Foundations drug service in Middlesbrough will be the first service to (re)introduce this approach in the UK but hopefully not the last.

Drug consumption rooms (DCRs) have been around for the last 30 years and are currently operational in several countries in Europe, North America and Australia. Similar to HAT, DCRs are clinical environments where heroin can be administered under medical supervision – although in the case of DCRs the heroin is bought on the illicit market by the individual using it rather than being prescribed.

Whether these types of initiative are made available across the country depends on two main issues. HAT and DCRs have been shown to be cost effective. Unfortunately, due to how budgets are managed in England it is hard to make these arguments as the one spending the money will not be the one making the savings. Local authorities are responsible for funding drug treatment but nearly all savings will be in the NHS, police, courts and prisons. With little to no savings for local authorities and billions of pounds cut from council budgets following a decade of austerity, it will require a shift to a more holistic view of public sector spending, and for those civil institutions to work together more closely.

Secondly, if we're serious about reducing drug deaths then something more fundamental will need to take place. We will need to move beyond just seeing the behaviour and start seeing the people behind it. We will need society, and in particular those with the ability to bring about change, to see those at risk of death as deserving of public services - without caveat. People who use drugs have a right to life, to be safely and securely housed, to have their health needs met. Rather than changes to drug use being a precondition for support, people should be able to benefit from society’s rights, opportunities and resources as freely as those who don’t (openly) use drugs. Eliminating social exclusion is likely to have more impact on the number of deaths than anything else we may be able to achieve.

The solution to reducing drug-related deaths isn’t clear and simple but we can’t let it continue to be wrong. If we value the tens of thousands of lives we’ll lose over the coming years we can’t keep on following the same well-trodden path and expect drug-related deaths to suddenly stop.

This article was written for The Vision Project by Jody Clark. Jody is the Associate Director of DHI, writing this article in a personal capacity.

If you are interested in this article, you may also be interested in finding out more about our adult drug and alcohol treatment services.

DHI has invited the author to write the above article. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, policies or otherwise of DHI.

The Vision Project is DHI's way of marking its 20th anniversary, not by looking backwards but by looking forwards and seeks a range of diverse views to really inform this process and develop its services for all.

Get news from Developing Health & Independence in your inbox. See our privacy policy.